Jordan Wears Sneakers, Too

By James Novick-Smith

Illustration Dustin O. Canalin

To whom much is given, much is expected. We’ve fomented a culture particularly primed to apply excessive scrutiny to the figures we’ve rightly or not put up on a pedestal. And it isn’t too hyperbolic to claim that among the many we’ve thrust into the limelight, no one has been examined in greater detail than Michael Jordan. The most famous athlete in history has been under the spotlight for the last 35+ years—lifetimes it feels, generations at the least—and every self-respecting sports fan, from the casual to the obsessive, has an opinion.

ESPN’s phenomenal new documentary, The Last Dance, chronicles everything that lead up to Jordan’s final year with the Chicago Bulls and has, again, pointedly brought him back into the public eye. With little to no live sports to satiate the masses, this 10-part series has rejuvenated spirited discussion about his career, 17 years after his retirement. While his accolades on the court are many and largely without reproach, it is his off-court legacy that has come starkly back into focus. Specifically, his relentless competitive streak and the impact it had on his leadership role and his lack of visible or meaningful activism. While I always welcome a healthy MJ vs. LeBron debate, in light of the renowned discussions spurred by The Last Dance, it’s time to more fully interrogate the antagonistic off-the-court critiques that, question Jordan’s personal morals and integrity.

The Last Dance has expertly woven contemporary interviews in-between incredibly intimate footage of Michael Jordan and the Bulls’ heyday and many of the revelations have been eye-opening. Specifically, the interviews with the relatively recalcitrant Michael have given viewers a peek inside his head, shedding light on his psyche and competitive drive; perhaps, most of all though, they’ve given him an opportunity to defend himself and provide his rationale for his actions (and inaction in some cases).

Although he had the last say over what was included in the final cut, Jordan didn’t necessarily have to strong-arm director Jason Hehir into painting a glowing picture of himself—a portrayal of one of the most competitive athletes of all time is to depict, again, generation’s worth of narrative, drama, and controversy.

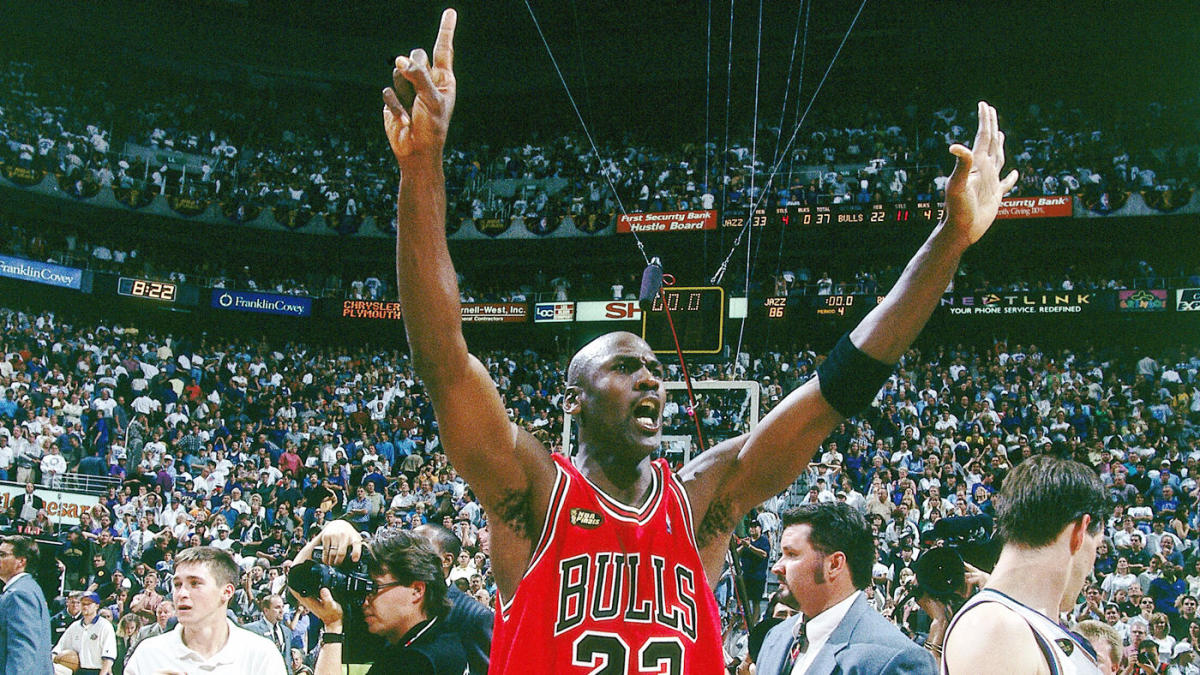

Image Courtesy of CBS Sports

Jordan himself says “Winning has a price. And leadership has a price.” What the doc portrays is a man who knew full well that he would be making more than a few enemies in order to become a living legend, and in particular, is at peace with his decisions. Jordan was never the nicest guy to his peers and was close with very few outside of his inner circle. But his goal was never to make friends; it was to win, which is perhaps what best sums up his personality. Winner. While his leadership style is unacceptable in most office settings, he knew what it took to get the most out of his basketball team and took on his leadership role without pause or remorse.

There are few men alive with the basketball abilities that Michael Jordan possessed, but everyone, he thought, could (or should try to, at the least) exert the same amount of intensity as he did. He led by example, shouldering the majority of the blame and the most acerbic critiques thrown at the Bulls, all while taking the hardest hits driving to the basket. “You can ask all of my teammates—the one thing about Michael Jordan was,” he said, “he never asked me to do something that he didn’t fucking do.” It’s an easy thing to lead when the way forward is clear and unhindered; when times get tough, people’s true characters are revealed and the peerless leaders take charge.

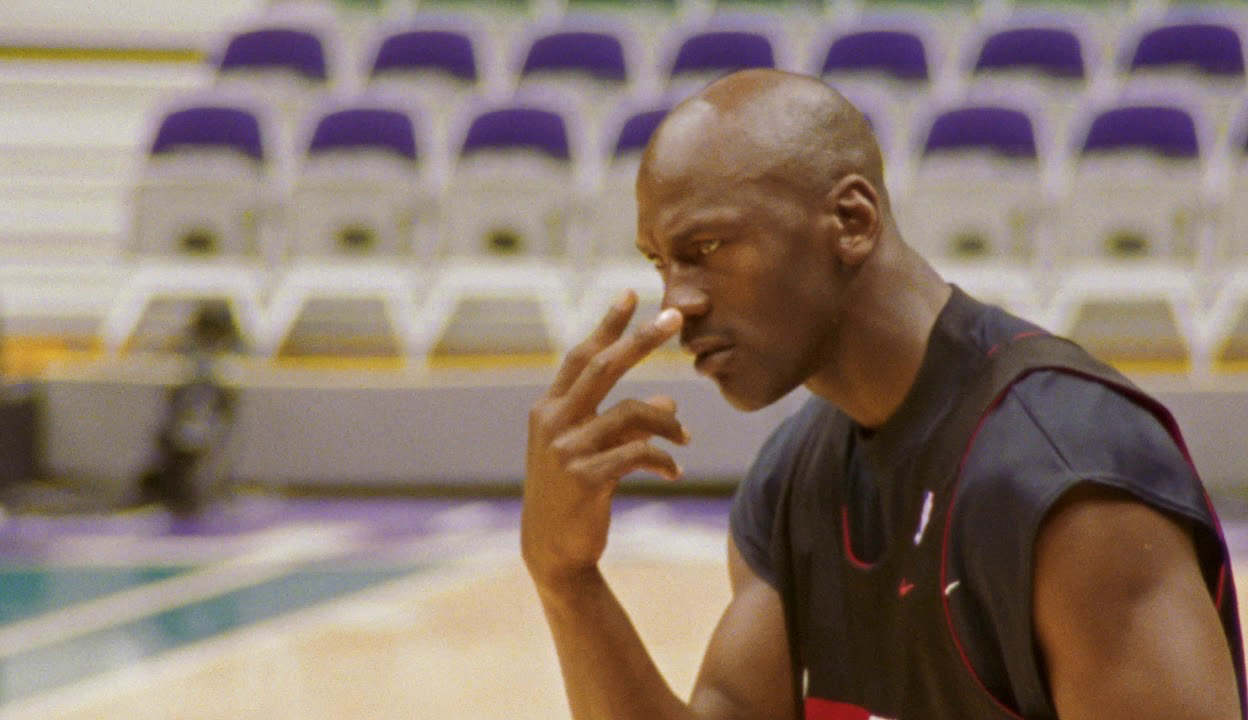

Image Courtesy of The Last Dance

People may have criticisms about his motivational techniques, and while both the occasional punches thrown and constant verbal lashings speak for themselves, so too do Jordan’s team accolades: An NCAA title; 6 NBA championships; 2 Olympic Gold Medals. He “pulled people along when they didn’t want to be pulled, challenged people when they didn’t want to be challenged,” but, at the same time, his teammates “didn’t have to endure all the things [he] endured.” Most players, at one point or another would, no doubt, take the heat from Mike if it meant they’d reach the basketball mountaintop.

People in this day and age love to look back at history and relitigate the moralities of past events, but the truth is, none of us were there inside the Bulls locker room. What The Last Dance has taught us is that none of Jordan’s contemporaries seem to hold too deep a grudge against him—except, of course, for Isiah Thomas. It’s a sports fans’ fallacy, but for the sake of the argument, let’s consider the opinions of the contemporaries who knew the man personally rather than leading with our own projections granted that we likewise acknowledge that memory is imperfect and history is written by the winners.

Amazing as his records are, they have not defined his global legacy nor his contributions to the culture. Michael didn’t just lead on the court; he was a trailblazer, in many ways, off the court, too, instrumental both in growing the NBA into the massive industry it is today and in bringing African-American culture further into the mainstream at the end of the 20th Century. Before he was ever a world-beater on the basketball court, few team sport athletes were making major money outside of their player contracts; it was the dual sport stars like Muhammad Ali, Bjorn Borg, and Arnold Palmer who received all the lucrative endorsement deals and had branded product lines to hawk to the masses.

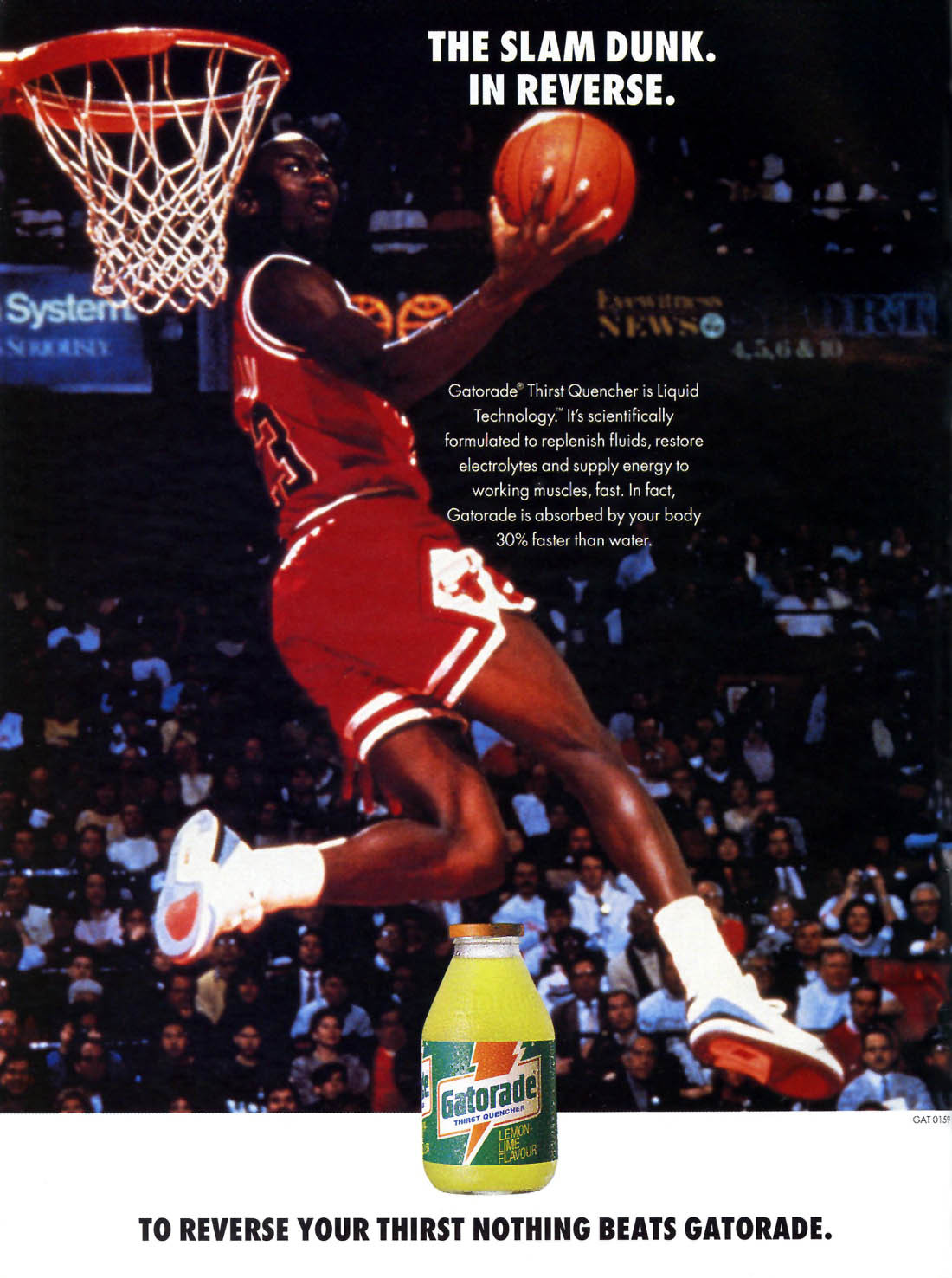

Image Courtesy of Gatorade

That all changed in an instant when Michael Jordan signed a $500,000-per-year deal with Nike (even though he preferred Adidas at the time) and launched his eponymous and now world-famous shoe brand, Air Jordan. While Nike expected to sell $3 million worth of Jordans in its first 4 years, they, instead, sold $126 million. Gatorade, McDonald’s, Hanes, and a plethora of other corporate sponsors soon followed suit, and, before long, he was the best marketing agent in the world. While he ultimately made $94 million on the court, he’s earned an estimated $1.7 BILLION over four decades away from basketball. As astonishing as that figure is, MJ’s monetary earnings don’t even tell the whole story of his impact on sports: In successfully marketing himself and his personal brand, he designed the blueprint that the generations of athletes hence have used to monetize their likeness for fame.

Air Jordan was undeniably a major part of the zeitgeist of the 1980s and ‘90s and is quite obviously much more than an athletic shoe brand; it’s a symbol of the proliferation of Black culture into the mainstream across America. Prior to the Air Jordan 1s, sneakers weren’t necessarily worn as an everyday shoe—and certainly not as a fashion statement—by most (read: white) Americans. But once Jordan started lighting it up with the 1s on his feet, every kid in America needed those shoes. In the late ‘80s, consumer options ballooned. Although Run-DMC had “My Adidas” and Converse released “The Weapon,” they were no match for Mike’s Air Jordans. For the first time ever, athletic shoes were a status symbol, and everyone from The Fresh Prince to Slash had a pair of Jordans.

While basketball, and by proxy, basketball sneakers, had well-established cultural appeal in the Black community, so too, did sneaker culture begin to reach a white audience. Although, instead of pandering exclusively to this newfound audience, Air Jordan tapped into Black culture to market to everyone, especially the young lack consumer. And with Mike getting buckets in his signature shoe and looking (nearly literally) fly doing it, the sneakers practically sold themselves. While the shoes weren’t cheap, they were an aspirational item that allowed anyone who wore them to be associated with greatness.

Image Courtesy of COMPLEX

Nike even tapped Spike Lee to direct the famous “It’s Gotta Be The Shoes” ad which eventually led to his own signature silhouette, the Spizike. While in many ways Nike fell into the same appropriative and exploitative tendencies of selling Black culture to a white audience that has historically plagued our society, Jordan personally has been handsomely rewarded by his investment. (He earned ~$130 million just in 2019 alone). Moreover, while MJ was one of the first Black athletes with a popular signature shoe in 1985, he opened the door for myriad other Black athletes since—from Bo Jackson to Giannis Antetokounmpo—to achieve footwear successes of their own, leveraging their fame to expand their personal brands.

One aspect of professional athletes that was true long before Jordan came around, and is even more true today, is the immense influence they wield given their broad societal appeal. The most well-respected athletes leverage their platforms to advocate for social justice; Michael Jordan, however, seems to have been more concerned with personal gain than activism. He restrained himself from engaging in community advocacy while he was playing and largely refused to take any stance that could be perceived as controversial.

In a friendly, intimate moment on the team bus that has haunted him for thirty years, MJ commented that “Republicans wear sneakers, too,” when asked why he wouldn’t openly support Harvey Gantt’s North Carolina senatorial campaign in 1990. Not only would Gantt have been the first African-American senator from N.C., but he was running against notorious racist Jesse Helms, a man who called the 1964 Civil Rights act “the single most dangerous piece of legislation ever introduced in the Congress.”

Jordan has since stated he didn’t want to make a comment about something about which he was uninformed, but his lack of speaking out is just as irreproachable today as it was back then. “I do commend Muhammad Ali for standing up for what he believed in,” says Jordan in The Last Dance, “but I never thought of myself as an activist. I thought of myself as a basketball player.” This justification, while short-sighted and too simplistic, speaks to a broader issue of the over-idolization of athletes in our society.

Jordan did not use his platform in a visible way to promote social causes like so many of his predecessors, but when he was playing there were few athletes who were. The late ‘80s and early ‘90s were a different time than the Civil Rights Era, when athletic activism was far more widespread. I challenge anyone reading this article to think back on that time and come up with a high-profile athlete—in any sport—who consistently engaged in activism. There aren’t many! I do not mean to say this as a means to explain away Jordan’s reticence, but simply to frame it through a contemporary lens.

There surely were several activists during Jordan’s era, but their stories are cautionary tales. Craig Hodges, one of Jordan’s teammates on the Bulls (1988-1992), attempted to advocate to stop the injustices he saw in the Black community during the Bulls’ 1991 post-championship trip to George H.W. Bush’s White House. Hodges, the reigning 3-time Three Point Contest champion, was waived by the Bulls shortly after and never received another NBA contract; he wasn’t even allowed to defend his title at the All-Star Game in 1992. In 1996, the NBA suspended Mahmoud Abdul-Raouf for staying in the locker room for the pre-game national anthem ceremony in protest of the rampant racism and oppression that the American flag represented to him. He, too, would never receive another NBA contract. Although both of these instances occurred after Jordan’s famous quip, they nevertheless speak to the broader social temperature during his era and the unforgiving climate of athletic activism.

The bottom line: Jordan kept his mouth shut, sullying his legacy as an activist while quietly stacking his money. He was looking out for him and him alone, certainly a selfish decision, but one that has paid dividends and has allowed him to reach heights that no other athlete had prior to or since. He is just the second Black owner in professional sports, setting a standard that others will undoubtedly follow. While he has spoken out since his retirement, both about Donald Sterling and police brutality, his outspokenness comes with a preface: “It's never going to be enough for everybody… because everybody has a preconceived idea for what I should do and what I shouldn't do.” While we should admire those athletes who speak out, rather than only denigrating those who don’t, let’s countenance their inaction. In this case, Jordan was playing the long game and it has clearly paid off for him in the most literal sense of the word.

Hindsight will always be 20/20, and it is extremely easy to look back on mistakes and lapses in judgment with contempt and scorn. Jordan’s lack of activism in 1990 was decried then and, perhaps, even more so today and it has clearly made an impact on him. In the wake of George Floyd’s murder at the hands of the Minneapolis Police Department, Michael wasted no time in pledging to donate $100 million to organizations that fight for racial equality and social justice and over the next ten years. He has learned that given his venerated position in society, regardless of his personal beliefs and actions, he is no longer allowed to keep his mouth shut, and must let the public know his stance on issues that affect everyone in our society.

“Jordan’s lack of activism in 1990 was decried then and, perhaps, even more so today and it has clearly made an impact on him.”

Ultimately, the uproar about Jordan’s activism or lack thereof has revealed a key issue with our views of athletes and how they use their platform. We overvalue their opinions about every possible issue or plight in society to the point where we get frustrated when they don’t speak out. For instance, why did LeBron James owe us his opinion on the protests in Hong Kong? As a society, we should not hold athletes to such a high standard and expect that the same level of near-perfection as they produce on the court or field; after all, they are only human, despite the otherworldy status their fans sometimes bestow on them.

Image Courtesy of Baseball Magazine

Image Courtesy of Baseball MagazineStill, we seem to have a double standard when it comes to athletic activism: Why is it that we mostly have gripes with the Black athletes who stay silent? What does it say about our society that white athletes aren’t held to the same high standards and scrutiny? To fix the biggest societal issues we have today, allyship is vital and yet the most famous white ally in sports is Branch Rickey, general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers and the man who broke the color barrier when he signed Jackie Robinson in 1945—over 70 years ago! Why are we not incensed that Jordan’s peers like John Stockton or Mark McGwire, or any other white athlete for that matter, never spoke out against racism, or advocated for social justice reform?

In order for our society to truly change for the better, we need universal buy-in, and that starts from the top. The recent outcry over Drew Brees’ tone-deaf opinion on NFL protests shows that our expectations of prominent white athletes is evolving, but actions will always speak louder than words. Statements are a good start, but we need to call for more white athletes to be active allies, not only supporting their Black peers but also fighting right alongside them on the front lines of the fight for racial justice.

Image Courtesy of ESPN

The Last Dance has been a godsend during quarantine, providing humor with new meme content and the closest thing we have to live sports. It’s refocused our gaze onto the legacy of Michael Jordan once again, except, this time, he has given himself a voice. In his words: “The way I go about my life is I set examples. If it inspires you? Great, I will continue to do that. If it doesn't? Then maybe I'm not the person you should be following." Born in 1995, I regrettably never saw MJ the Basketball God play, only the very human Michael Jordan, late of the Wizards (2001-2003). Still, I can still remember watching Space Jam on VHS over and over again until the tape wore down completely. The man has always been an incredibly inspiring figure for the entire world, and because of this, he has been the target of more criticism than nearly anyone else outside of certain presidents and maybe some pop stars. Can you imagine the flak he would’ve received if Twitter had existed during his prime?

Image Courtesy of The Last Dance

In watching this documentary, I’ve fully come to understand the common ground that sports provide—they are the last cultural monolith we have in an increasingly fractured American society. And while it isn’t the sport that has captured our collective imagination but the stars who play, these men and women are aspirational figures but not gods, and should be treated as such. Michael Jordan has shouldered an immense burden throughout his career, and given the lifetime (or is it generations?) of entertainment and inspiration he’s produced, MJ wears sneakers, too. Today, he may be changing his attitude a bit more, perhaps as an attonement for past shortcomings, large and small. If that’s a show of conscience, then we can likewise continue to appreciate him for the basketball genius and American icon that he is.︎