Looking Back to Move Forward:

Archiving & Collecting from Elders

By Janelle Wallace

Illustration by Bernard Rollins

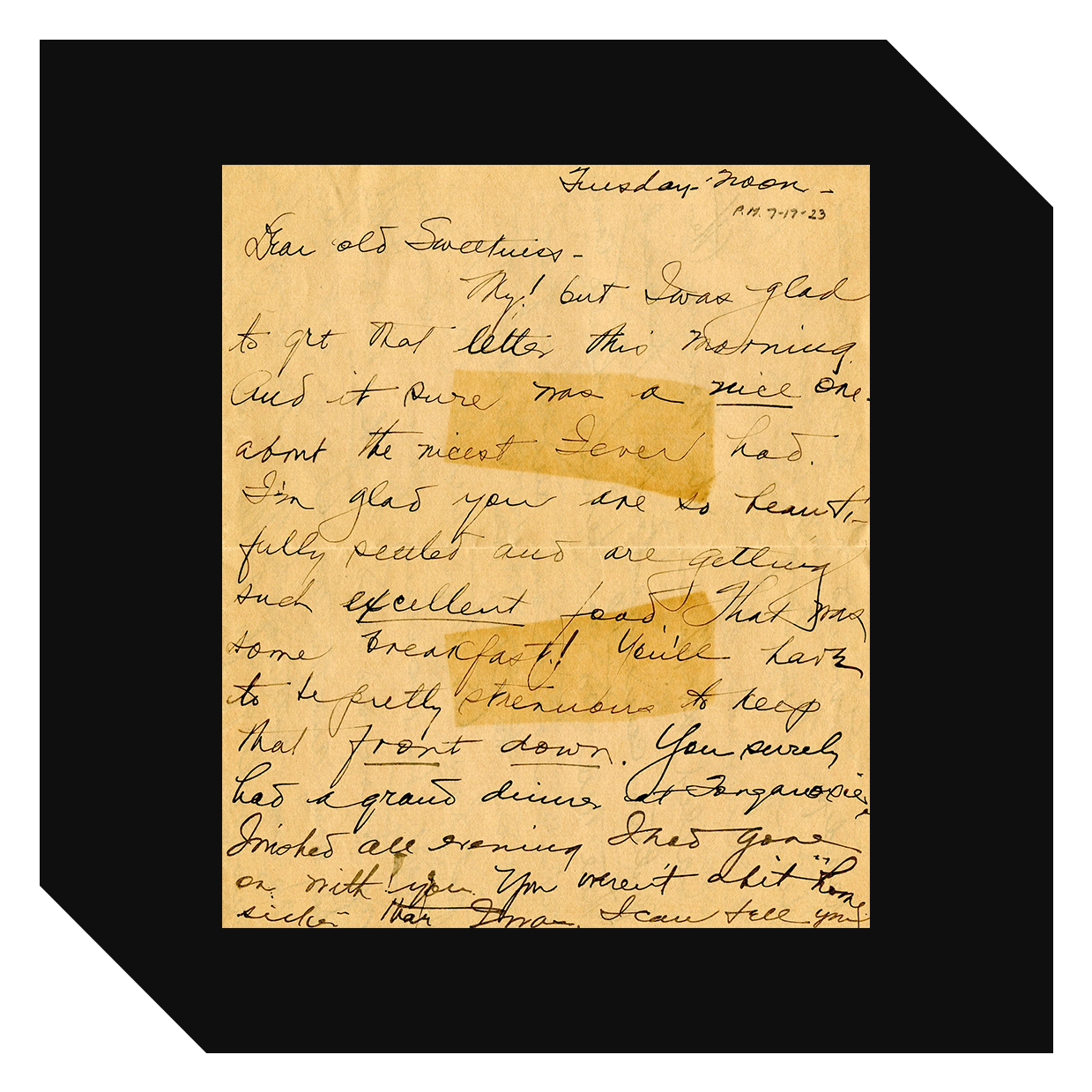

My father has an old black and white picture of a man sitting in a wooden chair dressed in a dark suit, white shirt, and porkpie hat in front of a small, wooden house. If I had to guess, I’d say the photo was taken in the early 1920s. The picture was found among my grandfather’s belongings long after he passed. We believe the man in the photo is my great-grandfather, but we’ll never know for sure. We have no more living relatives who would know.

My recent interest in who and what is remembered was sparked by friend and photographer Daniela Spector’s project I Forbid You to Forget Me—a cataloguing of her mother’s belongings after her passing. It’s an examination of the solace found in the uncovering of stories, relics, and rituals of someone so close.

Ma’s Tchotchkes; Daniela Spector — I Forbid You to Forget Me

Ma’s Tchotchkes; Daniela Spector — I Forbid You to Forget Me

Keeping and maintaining these family relics and the context to go along with them, is imperative, especially for the Black community—a community with a long history of having their stories discounted and dismissed. By creating, selecting, and preserving our own records, it becomes possible to form a more complete and accurate history of our family members’ lives and experiences. Thus, capturing this history from our elders before it disappears with them.

Faces in old photo albums will go unrecognized without context from forebearers. Thanksgiving Dinner recipes passed down from earlier generations will become a mere memory. All of these keepsakes come with a backstory that deserves to be remembered.

Rosa Parks’ Pancake Recipe

Rosa Parks’ Pancake RecipeWe must have conversations with our elders and record their accounts and memories for future generations. In times like these, we must safeguard our family narratives. Battling a pandemic that finds the elderly the most vulnerable and with African-Americans dying at an alarmingly higher rate than others, we must consider the ramifications of these compounded losses in mass. What recourse exists when the person who held the family’s history is gone?

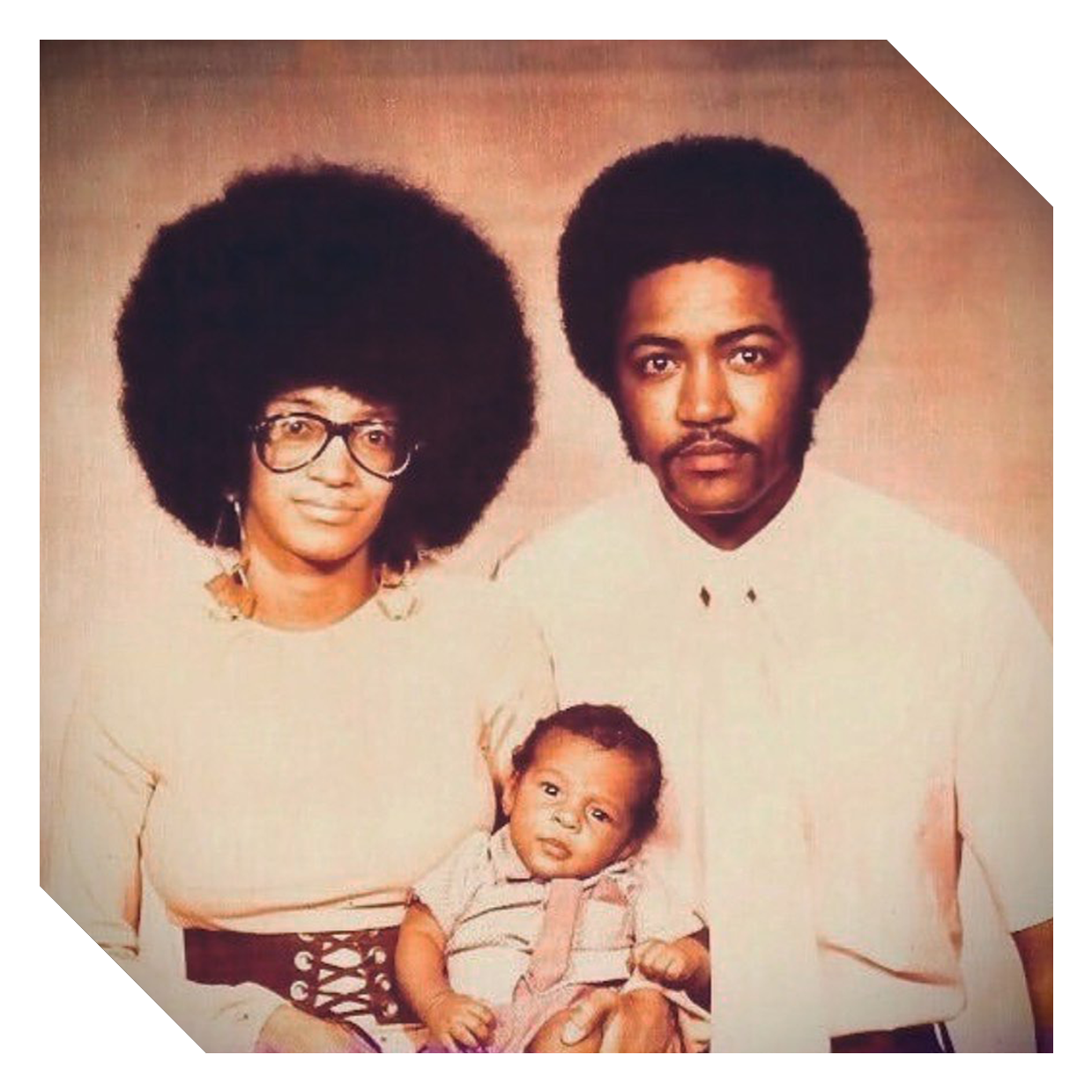

Outlets such as Blvck Vrchives, featuring archival histories and modern-day stories from across the African diaspora, offers a glimpse into the rich stories of everyday Black life and underscores the importance of preserving our imagery. They even allow follower submissions of family photos and stories to archive and share on their platforms to better illustrate the importance of the everyday story. Archives even have the potential to inspire art as is the case with renowned photographer Micaiah Carter’s work—directly motivated by his father’s photography archive.

Image Courtesy of: Blvck Vrchives

Image Courtesy of: Blvck Vrchives

One of my favorite platforms devoted to the retelling of unsung history is The New York Times’ Overlooked initiative, a history project recalling the lives of those who were left out of The Times’ obituary pages since 1851. Beginning in March of 2018, the Times has made a concerted effort to diversify those they honor in the obits since the vast majority chronicled the lives of white men. Prior to Overlooked, important stories were going untold with figures such as Ida B. Wells and Nella Larsen only having their stories told by the paper of record decades after their passing.

The National Museum of African-American History and Culture also has a program devoted to archiving the everyday Black experience. The Community Curation Program’s goal is to bridge the generational divide in African-American communities by enabling participants to preserve and share their stories via audio, video, photography, and other mediums into a central repository. Selections from the CCP are then featured in the Museum’s Robert Frederick Smith Explore Your Family History Center which allows on-site visitors to discover diverse family stories while enabling off-site participants to visit the Center remotely. The program offers an opportunity to celebrate African-American history at the community level.

In archivist Dominique Luster’s Tedx Talk, she asks, “If your history isn’t recorded and preserved, did you exist?” And while the answer is yes, it does make you consider how you ensure your history lives on. Modern photographers and portrait-painters add to the conversation around being remembered and capturing our history in the now, all for future preservation. Paper Monday describes itself as a producer of timeless portraits and in-depth visual stories, while painter Jas Knight creates intricate portraits resulting in future relics rooted in 16th- and 17th-Century realism.

Image Courtesy of: Paper Monday

Image Courtesy of: Paper Monday

So, how would you like to be remembered? What measures are you currently taking to ensure that history is unshakable? I’d argue that the age of social media has lessened the burden of archiving on future generations. What is there to uncover and retell when every highlight of our existence lives across some combination of Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook? As much criticism as our online behaviors receive, perhaps the archive it holds of our lives is enough to offset the negative.︎